Apple implemented device encryption in the iPhone 3GS, improving its odds of being considered for enterprise deployment.

Apple implemented device encryption in the iPhone 3GS, improving its odds of being considered for enterprise deployment.

However, users using Exchange ActiveSync (EAS) to connect to their Exchange 2007 mailboxes couldn’t take advantage of it, even when encryption was required by an Exchange ActiveSync Mailbox Policy, because the device didn’t tell Exchange it can support encryption.

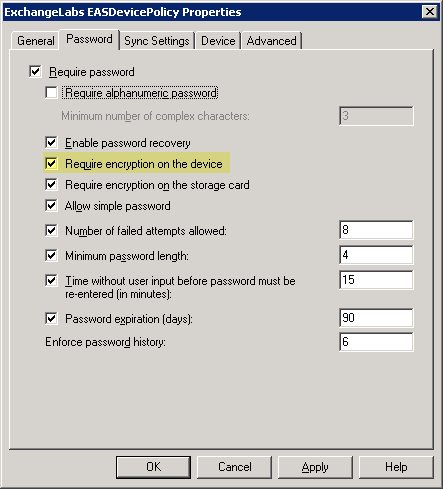

With the latest iPhone OS 3.1 update, iPhones start identifying themselves correctly, and if the ActiveSync policy configured by the administrator requires device encryption (see Figure 1 below), data on the device is encrypted. That’s great news— unless you happen to have an older iPhone. If you’re using the (Original/Classic/2G/1G?) iPhone , or the iPhone 3G, and device encryption is required, you will be unable to log on to your mailbox.

This is great for iPhone 3GS users, who can now be more secure than they previously were. Users of legacy iPhones can either buy an iPhone 3GS to have their data stored securely on the device, or downgrade, somehow, to the previous version of iPhone OS. I’m not sure if a downgrade is possible, or if you’ll need to take your iPhone to an Apple store to have it downgraded. (Incidentally, the iPhone user in the family was in no rush to upgrade to iPhone OS 3.1, and can’t really stand Apple’s iTunes software.)

Figure 1: Enforcing device encryption using an ActiveSync Mailbox Policy in Exchange 2007

News.com’s Jim Dalrymple suggests in Apple explains iPhone OS 3.1 Exchange changes:

If you already upgraded to iPhone OS 3.1 on an iPhone or iPhone 3G and connect to an Exchange 2007 server, you can ask that the IT admin turn off the hardware encryption requirement for those devices.

Good luck with that!

Update: Interestingly, the above suggestion is actually what Apple recommends in its knowledgebase article TS2941: iPhone OS 3.1: ‘Policy Requirement’ error when adding Microsoft Exchange account. Specifically:

To reestablish syncing, have your Exchange Server administrator change the mailbox policy to no longer require device encryption.

In a nutshell— lower security to allow older iPhones to sync. If you use the same ActiveSync policy for all users, this also lowers security for all mobile devices in your organization!

If you want to read InfoWorld (the dabbling-in-sensationalism publication I call MAD magazine of tech journalism and others equate with tabloid journalism) executive editor Galen Gruman’s – should I say, more strongly worded take on it, here it is.

It turns out that Apple’s iPhone 3.1 OS fix of a serious security issue — falsely reporting to Exchange servers that pre-3G S iPhones and iPod Touches had on-device encryption — wasn’t the first such policy falsehood that Apple has quietly fixed in an OS upgrade. It fixed a similar lie in its June iPhone OS 3.0 update. Before that update, the iPhone falsely reported its adherence to VPN policies, specifically those that confirm the device is not saving the VPN password (so users are forced to enter it manually). Until the iPhone 3.0 OS update, users could save VPN passwords on their Apple devices, yet the iPhone OS would report to the VPN server that the passwords were not being saved.

I resisted highlighting that entire quote. Needless to say, if this is indeed true and not merely InfoWorld’s interesting interpretation and reporting of facts— it makes Apple’s tall claims of being “highly secure by design” and “secure from day 1” across its product line (OS X, Safari browser, the iPhone and Apples online services) worth every bit of suspicion, skepticism, and scrutiny they deserve.

The InfoWorld article ends with:

IT organizations can also consider using third-party mobile management tools that enforce security and compliance policies; several now support the iPhone to varying degrees, including those from Good Technology, MobileIron, and Zenprise.

Although mobile device management products such as those mentioned above can make it cost-effective to manage large number of mobile devices, improve service levels, lower time to resolution, and to some extent help with securing them, I doubt any of them can actually determine if what the device reports about its capabilities or status is really true. To read rest of the article, head over to The other iPhone lie: VPN policy support on InfoWorld.com.

Does the iPhone meet the bar for enterprise deployment? Do you allow iPhone users to connect to your Exchange server?

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

Our security team did not approve iPhones when Apple introduced Exchange Server connectivity in the iPhone, and it seems their stand is validated by Apple's latest snafu. Apple doesn't get the enterprise.

MS Exchange Team Blog states:

"Additionally, before iPhone OS 3.1, these devices did not communicate their policy status correctly, resulting in the devices being able to connect to Exchange Server, even if your Exchange ActiveSync policy required device encryption and did not allow non-provisionable devices."

http://msexchangeteam.com/archive/2009/09/22/452592.aspx

Does it going to help the security purpose? I don't think so. Because ultimately every intruder finds the way to get in.

@gift ideas: Going by that logic, you probably don't bother to lock your car or your home either? :)

It's true determined intruders with adequate resources will find a way to get in. As owner or guardian of resources, it's the job of organizations and security departments to deter the less determined or "casual" intruders, and make it as difficult as possible for more determined intruders to compromise information/assets being protected, without significant adverse impact to business processes.

It is my understanding that the pre 3.1 OS did not falsely report that it was compliant, rather, it didn't report that it wasn't. This is a very important distinction. If the iPhone indeed was intentionally reporting a false encryption status, then a strong argument exists that Apple facilitated what could be construed as hacking (in the sense that they knowingly and intentionally assisted people in bypassing security for the purpose of gaining access to a system). ON THE OTHER HAND, if Microsoft and other manufacturers allowed a device to gain access by simply not responding to an encryption challenge, then the real blame falls on them; and the same argument regarding facilitating improper access by an intentional and known exploit can be made.

Someone is certainly guilty of a major and intentional security breech here, but we need a definitive answer on how the older iPhones were responding (or not responding) before we know which way to point our fingers.

I am not an Apple fanboy and I'm not a Microsoft muppett, I hope all of us can step back from our corporate prejudice and address this and other issues with a logical approach.